Mattel recently faced a barrage of criticism after a blogger excoriated them for the story and language of the book Barbie: I Can Be A Computer Engineer. The book, in Barbie’s “I Can Be…” series and published in 2010, has now been discontinued. But it continues to provide an interesting look at how, while some comments and word choices may seem benign individually, when combined to represent the language of a culture, it can be seen more clearly as a subtle yet endemic problem.

Mattel recently faced a barrage of criticism after a blogger excoriated them for the story and language of the book Barbie: I Can Be A Computer Engineer. The book, in Barbie’s “I Can Be…” series and published in 2010, has now been discontinued. But it continues to provide an interesting look at how, while some comments and word choices may seem benign individually, when combined to represent the language of a culture, it can be seen more clearly as a subtle yet endemic problem.

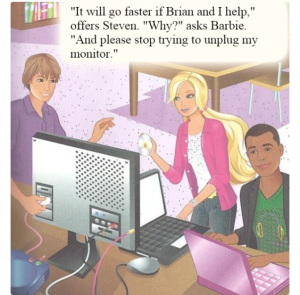

Putting aside the narrative—Barbie essentially breaks her sister Skipper’s computer, then has some male friends fix it while she enjoys the credit—it is disappointing that the language used was not more carefully vetted by Mattel. Blogger and IT professional Karen Lopez provided an excellent “refactoring” of the text of the book:

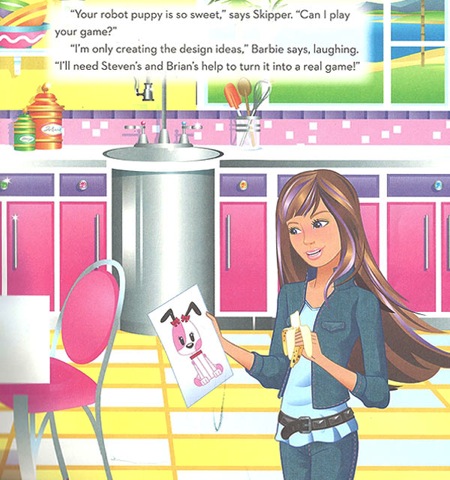

In the page shown above, when Skipper asks if she can play the video game Barbie is working on, Barbie says:

“I’m only creating the design ideas,” Barbie says, laughing. “I’ll need Steven’s and Brian’s help to turn it into a real game.”

This not only demeans the designer’s vital role in game creation, but makes Barbie sound less than competent. Lopez rewrites the line:

“Not yet,” explains Barbie. “I need to finish the design, then work with Steven and Brian to turn it into a game.”

The meaning of both versions is largely the same, but the belittling terms “only,” “need” and “help” have been removed or replaced. And rather than “laughing” at Skipper’s assumption that her game might actually be functional, she instead “explains” that design is one part of many in the process of game creation.

If you’ve read through the original Barbie: I Can Be A Computer Engineer, whether on Pamela Ribon’s site or elsewhere, Casey Fiesler‘s “remix” of the book (reposted here on Slate) is a refreshing follow-up read. (Computing PhD candidate Fiesler is on the legal committee for the Organization for Transformative Works, making her remix of particular interest in regard to modern issues of copyright law. To quote from her blog, “One of my favorite things about remix: If you don’t like the narrative, change it!”)

Barbie has issued an apology on Facebook, the book’s author has commented on the controversy, and Mattel has removed the book from online distribution venues. Regardless, the internet has continued to have fun creating alternate versions of it. You can even make your own!

While Barbie has been no stranger to feminist debate over her long life (remember “math is hard“?) many people have been surprised at the quality and entertainment value of some other recent Barbie-related media, such as the 2009 DVD Musketeer in Pink (Barbie is D’Artagnan!) and the not-awful short video series “Barbie Life in the Dreamhouse,” now in its fifth season.

While Barbie has been no stranger to feminist debate over her long life (remember “math is hard“?) many people have been surprised at the quality and entertainment value of some other recent Barbie-related media, such as the 2009 DVD Musketeer in Pink (Barbie is D’Artagnan!) and the not-awful short video series “Barbie Life in the Dreamhouse,” now in its fifth season.